The Investment casting technology, also known as lost wax process is no stranger to the Indian sub-continent. The art was vastly practiced in ancient India for casting Idols and art objects mostly in copper alloys. The lost-wax method is well -documented in ancient Indian literary sources. The Silpasastras, a text from the Gupta Period, contains detailed information about casting images in metal. The fifth-century AD Vishnusamhita, an appendix to the Vishnu Purana, refers directly to the modeling of wax for making metal objects in chapter XIV: "if an image is to be made of metal, it must first be made of wax." [Chapter 68 of the ancient Sanskrit] text Mānasāra Silpa details casting idols in wax and is entitled "Maduchchhista vidhānam", or "lost wax method".

The Manasollasa (also known as the Abhilasitartha chintamani) was allegedly written by King Bhulokamalla Somesvara of the Chalukya dynasty of Kalyani in AD 1124-1125, and also provides detail about lost-wax and other casting processes. In a 16th-century treatise, the Uttarabhaga of the Silparatna written by Srikumara, verses 32 to 52 of Chapter 2 ("Linga lakshanam") give detailed instructions on making a hollow casting.

Metalcasting began in India around 3500 BC in the Mohenjodaro area, which produced earliest known lost-wax casting, the Indian bronze figurine named the "dancing girl" that dates back nearly 5,000 years to the Harappan period.

Producing images by the lost-wax process reached its peak during from 750 AD to 1100 AD, and still remained prevalent in south India between 1500 AD and 1850. The technique still remains well practiced throughout India, as well as neighbouring countries Nepal, Tibet, Ceylon, Burma and Siam. During the second world war, the process was upgraded for industrilisation.

-

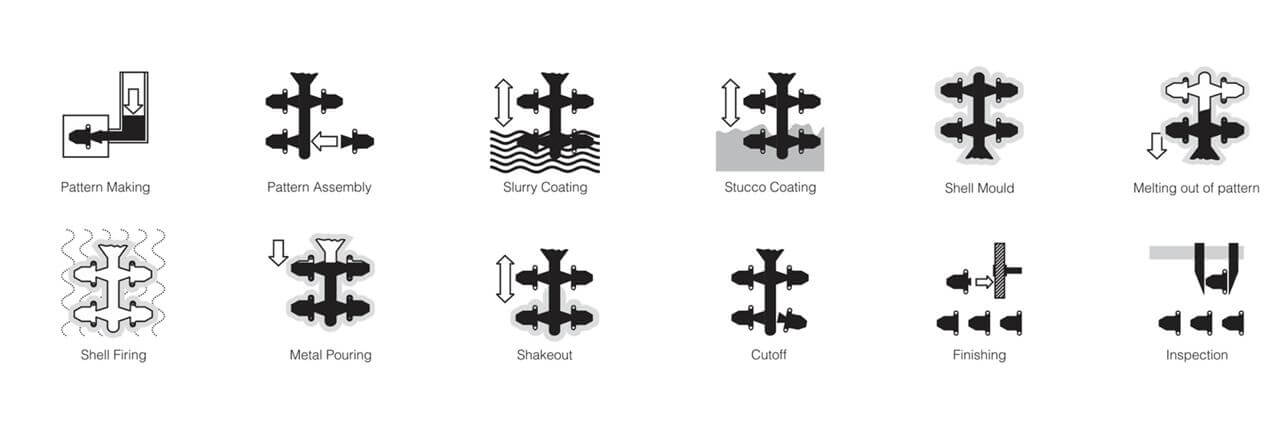

A metal die is used to produce an expendable pattern, now almost universally a complex blends of resin, filler and wax. Precision internal cavities in the casting are obtained using preformed ceramic or water soluble cores which are located in the wax die prior to injection or in a preformed cavity in a wax pattern.

-

Patterns are mounted onto a runner system to give an assembly ready for subsequent coating with refractory.

-

The wax assembly is then 'invested' (coated) with a refractory. The majority of industrial investment casting is based on the ceramic shell process, The wax assembly is dipped into a thin refractory slurry. After draining, fine grains of refractory are deposited onto the damp surface, providing a coating.

-

When the primary coat has hardened or set, cycles of dipping and 'sanding' build up the thickness of the invested material, providing a refractory shell which, when fully hardened, is strong enough to hold the liquid metal during casting. Robots are commonly used nowadays for this shelling operation.

-

After the investing process, the wax pattern is removed thermally or chemically. Steam autoclaving is usual.

-

Any residual wax is eliminated by heating the mould to a high temperature, which also completes necessary chemical and physical changes in the refractories.

-

Investment casting melting techniques are similar to standard foundry industry methods but, for many of the advanced nickel superalloys, vacuum melting/casting is essential.

-

When the mould is sufficiently cool, it is removed to leave the castings.

-

These can then be taken from the runner system and finished according to customer requirements.

-

Modern investment casting is a precision shaping technique producing metal components cast to precise shape, with accurate dimensions and excellent surface finish.

Investment casting is one of the highly valued processes for its ability to produce components with accuracy, repeatability, versatility, and integrity in a variety of metals and high-performance alloys.

There are ten basic steps in the investment casting process.

In essence, it is the archetype of near net shape casting, reducing metal wastage, conserving raw material and minimising the need for (usually costly) post-casting machining.

-

Freedom of design

-

Choice of alloys

-

Sizes from a few mm to over 1000 cubic mm

-

Generally Weight Ranges from Few Grams to 250 Kgs.

-

Consistent dimensions and properties

-

General Tolerances as per DIN_EN_ISO_8062 DCTG 4 to 6 or VDG P690 D1 or D2.

-

Minimum wall thickness of 1.5mm

-

Surface finish from Ra 3.2 to Ra 6.3 and better possible

-

Prototype or mass production quantities possible